| Home |

| Glossary |

| Lobstering |

| Some Facts |

| Handling Gear |

| Wildlife |

| Tools |

| A Day at Sea |

| The Boat |

| Lobsters |

| Facts |

| Molting |

| Eggers |

| Oversized |

| The Sea |

| About Tides |

| Misc |

| Credits |

| Site Policy |

| The Author |

| Today's Hi/Lo Tides |

01/29/26

00:53 0.779 L

07:19 9.512 H

13:52 -0.222 L

20:11 7.958 H

Station: Fort Point, NH

Station-local tide times. Height in Feet (MLLW).

Data are predictions supplied by the NOAA Tidal Predictions

Web Service.

Last updated:

01/29/26 05:59 UTC |

Some Lobstering Tools

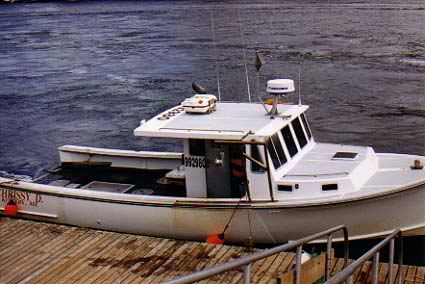

The 'Chrissy D.'. A fine boat, but not cheap. As anyone who owns a saltwater vessel will attest to, they are expensive to keep. They need constant maintenance and represent substantial overhead. As they say, "Sure, I have a boat. It's that hole in the water where all my money goes.". |

The device used to measure the carapace of a lobster. If the carapace fits within the smaller (top) notch, the animal is too small to take. If the carapcae is larger than the larger (bottom) notch, it is an over-sized animal and may not be taken in Maine. |

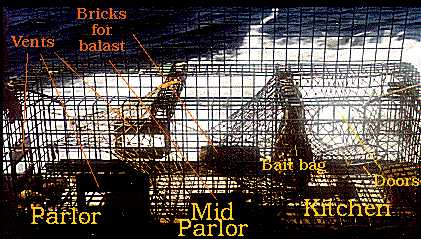

Each chamber of the trap is seperated by a cone-like entrance of netting which makes it easy for the animals to move deeper into the trap (toward the left), but more difficult to move back into the kitchen where the doors are. Well, that's the theory, anyways. |

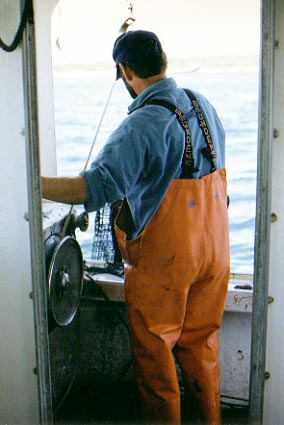

The hauler. A buoy is snared with a gaff hook and the line is passed over the 'snatch block' (hanging down). The line is then passed over the hydrolic 'pot hauler' (bottom left). When the hauler is turned on, the line is pulled in by the pot hauler. The hauler is stopped when the trap is close enough to be brought aboard, then restarted to retrieve the next trap. |

| The hauler is a dangerous piece of equipment. Fingers have been lost by getting caught between the line and the pinch roller. One fisherman using an older hauler got his arm caught so badly he was forced to cut it off to free himself. He was out working alone. | |

This artist's interpretation shows the deployment of a trawl on the sea bottom. It is not to scale. |

|

| The more traps on the line, the further the distance between the buoys. On large deep-water boats it is not uncommon to run 40-trap trawls where there is almost a mile between the buoys. | |